|

| More than one hundred years of Film Sizes |

One hundred years of cinema is also due to acceptance of one standard gauge. Whereas film equipment has undergone drastic changes in the course of a century it is a little miracle that 35mm has remained the universally accepted film size. If film had followed the same course as video, with its continuing change of systems, the development might have been delayed considerably.

|

We owe the format to a great extent to Edison (see photo) - in fact 35mm was called the Edison size before.

![]() Click on icon for Monkeyshines Edison film strip of 1890

Click on icon for Monkeyshines Edison film strip of 1890

![]() Edison Kinetograph film strip of June 18th,1891 (click)

Edison Kinetograph film strip of June 18th,1891 (click)

In May 1889 Thomas Edison had ordered a Kodak camera from the Eastman Company and was apparently fascinated by the 70mm roll of film used. Thereupon W.K.L.Dickson of his laboratory ordered a roll of film of 1 3/8"(ca. 35 mm) width from Eastman. This was half the film size used in Eastman Kodak cameras. It was to be used in a new type of Kinetoscope for moving images on a strip of celluloid film, which could be viewed by one person at the time.

|

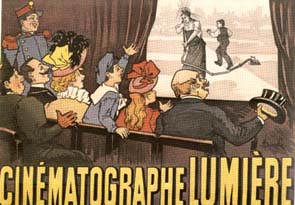

The Lumière brothers introduced in March 1895 their Cinématographe for 35mm film, which was also used at their first public show of 28 December of that year. Their strip of film had only one round hole per image, whereas Edison used four rectangular perforations per frame.

Even at that time there was already a variety of widths:

|

|

The abovementioned William Dickson, after leaving Edison, used 2 3/4" (70 mm) for his Mutoscope &

Biograph Company' productions to avert Edison's patent rights. Cameramen of this company

travelled all over Europe to produce documentaries of a remarkable image quality.

Widescreen also proved excellently suitable for other subjects.

|

In 1897 more than 10.000 feet of 63mm film was shot of the then famous box match between Corbett and Fitzsimmons.

One of the problems to be dealt with was the strength of the film base. Because film is pulled through the filmgate in short strokes it comes under high tension. Therefore perforations were torn time and again. Eastman overcame this weakness by doubling the thickness of the nitrate base, which was normally used for film packs from 1896 onward.

By the turn of the century film appeared to become big business. the struggle for the monopoly of the patents intensified. To avoid lengthy court cases the nine major producers of the time decided to pool their rights in the Motion Pictures Patents Company in 1909. This consortium threatened to outlaw outsiders from further film production. Despite the general outcry one favourable effect was that 35mm became standardized to Bell & Howell specifications. It was adopted a.o. by the Congrès International des Editeurs de Films in Paris in the same year. It was named standard-size stock, in Germany Normalfilm and in France pélicule format standard. Eastman Kodak became the chief film supplier (see 1912 ad).

This does not imply that no further attempts were being made to introduce other gauges. The standard size was besieged continuously for reasons of economy, projection quality or aesthetic design.

A fierce competition raged in the amateur market. Economy and dimensions were the chief ingredients. The public had to be won over by relative inexpensiveness. Amateur film was usually cut from 35 mm professional raw stock , that was produced in large quantities and therefore economical to buy. The film was cut in two or three lengths - the substandard size, or "Schmalfilm" in Germany.

The first attempt was demonstrated in England by

Birt Acres in 1898. His

camera, projector at the same time, the Birtac, used 17½ mm size with perforations on one side.

|

|

In the same year J.A.Prestwich introduced 13mm equipment, but little was heard of it since.

|

|

More succesful was Heinrich Ernemann, who introduced in 1903 the Kino I. It used the same film as the Biokam. This apparatus could also be used for both taking and projecting pictures - a combination which has been experimented with for years without much success, lately by the American Wittnauer Cine-Twin 8mm set.

In 1900 Gaumont-Demeny ventured with an unusual size: 15mm, with center perforation. The Chrono de Poche did not make it either. Nowadays it is a rarity. In the same year another French firm introduced the Mirograph which used an equally odd size: 20 mm. It had on one side notches instead of perforations. I have yet to see one single specimen.

In the United States the first projector using non-standard film appeared around 1902. This home cinema used a carbide lamp. It was called the Vitak and used 17,5mm film. A few years later another projector appeared with a similar appearance. It was the Ikonograph, using 17,5mm film with a large center perforation.

In 1923 11,5mm was re-introduced in the USA with the Duplex projector.

In 1897 a fierce fire destroyed the cinema pavillion of a charity bazar in Paris, which took the lives of 124 people. It is no surprise that an immediate search was opened for a replacement of the highly inflammable cellulose nitrate stock. In 1908 the first non-flam acetate film was marketed. It took decennia of perfection before it could supplant the old stock. Only in 1950 the tri-acetate film could be considered equal to nitrate film. However, for amateur films it was employed right after its invention.

|

|

In 1912 Edison introduced the Home Kinetoscope for safety film. It employed yet another size: 22mm. It had three rows of images sized 4 x 6mm, separated by two rows of perforations. One column of images was cranked foreward, the middle row backward, and the third row forward again. A camera was never produced. Films from 10 to 15 meter lengths in special containers were for rent from Edison depots or by mail.

Home Kinetoscope show (click)

|

|

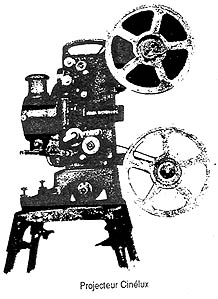

In 1931 Cinelux film projectors were introduced, a silent and sound model. A highly unusual 24mm unperforated Ozaphan film size was being used, the mechanism being a beater movement.

|

|

In 1912 Pathé introduced with far more success a 28mm size for safety film. The width deviated in order to prevent flammable normal sized film be used for the projector, the Pathé Kok (see image).

|

|

When during WW1 imports from France into the U.S.A. came to a halt Victor introduced their Safety and Home Cinema projectors for 28mm films perforated with three perforations per frame on both sides.

|

Pathé's distributor W.B.Cook designed a completely new motorized projector, the New Premier Pathescope (see photo). Not many were sold, however. Keystone and other manufacturers also introduced a 28mm projector, but reverted soon again to the 35mm size.

The Pathé Kok projector (The name was taken from from the newly patented logo of a cock)

was equipped usually with a dynamo. So it could be used on the not yet electrified countryside.

At the same time 28mm cameras were marketed. The emphasis was on showing theatrical films

copied from the large film library of Pathé, however.

Initially the new size seemed to do well and was accepted as a standard size for the home

cinema. By 1918 10.000 projectors were sold.

The projector enjoyed quite some popularity. In the United States 28mm was accepted as a standard size for portable film projectors by the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. 935 Titles were for rent.

Later developments made the format decline in popularity. Yet the Kok projectors are a showpiece in a collection nowadays, especially so because of its splendid design resembling a robust old-time sewing machine.

Besides emulsion on film base experiments were carried out with celluloid and glass plates. There was still a fierce competition between the magic lantern with its non-inflammable glass slides and the vulnerable film stock.

|

|

Yet, undaunted, The Aladdin Cine Products Co. ('from the Pictures Development Co., Toledo, Ohio, USA') produced a similar experimental series of discs of local subjects, but fared a fate even worse than Spirograph.

All these curious attempts make a fine hunting field for the collector nowadays. A Kammatograph was auctioned by Christies for £ 3850 in 1993 and may be worth more now.

|

Special Duplex projector lenses were to be made available to project the 10 x 19mm half frame onto the screen.

I have a brochure but have been unable to find any reference that the system was seriously considered, or the Duplex lenses ever made available.

|

Another proposal came in 1922 for a 42 mm size to accomodate a 7mm optical sound track to existing 35mm film by the German Triergon company.

|

After thirty years of experimentation with different widths in 1922 one was marketed which stood a better chance. In December 1922 Pathé introduced its home cinema, Le Cinéma chez soi, called the Pathé Baby.

|

Between the perforations of 35mm film three rows of 9,5mm were slit (see image).

The projector came first. Its transportation mechanism was almost identical to the Lumière

Cinématograph of 1895. The apparatus projected a steady image of amazing clarity

considering the lamp of 6 Watt. Cassettes with lengths of 9 or 15 meter 9,5mm film could be

bought or rented from depots. These films stood out by their great definition. They were

reduced from Pathé's considerable 35mm archive. Subjects included newsreels, documentaries,

comedies and feature films. Some were colored by a stencil imprint method. An ingenuous

system was used to prolong the projection time. By means of notches in the film a mechanism

was set into motion in the projector by which certain images - titles or close-ups - could be

frozen for a few seconds.

|

In 1923 a camera with hand crank was marketed. It being small in size, handy and economical, made it popular in a short time. It was for the first time that amateur film gained a wider acceptance. It is estimated that some 300.000 projectors were sold. What happened to all of them is another matter. They are not that often being offered for sale nowadays.

As a result of later developments the size never became popular in the U.S.A. In Europe it was. Even in Japan imitations of 9,5mm movie cameras and projectors were manufactured before the war (Cine Rola). In 1938 9,5mm sound film was introduced with the Pathé Vox sound-projector.

It may come as a surprise to some but 9,5 mm still has a following. Cameras and projectors are

still manufactured, or more precisely, modern equipment is being converted to this size. Films

are still re-perforated by some firms and developing facilities are available, given enough

patience.

Internationally 9,5mm fans form a closely knit community holding yearly global gatherings. The

best nine-five films of that year are projected then.

Kodak could not lag behind Pathé. John Capstaff of the Kodak laboratories had already been experimenting with another size. They had come to the conclusion that 10mm was the minimum image width for acceptable quality. Perforations on both sides would occupy another 6mm, making a total of 16mm. This gauge had the additional advantage that flammable 35mm stock could not not be slit in half for amateur use.

In 1923 16mm was introduced. In the battle for the amateur market Pathé boasted that its size was cheaper because of its economical use of the film width. Its prices suited all(?) purses. In their sales' slogans Pathé boasted that 9,5mm had almost the same frame size of 16mm at the price of 8mm.

Kodak opposed that middle perforations could cause stripes over the image. Moreover if the projector claw failed to hit the perforation accurately the images could easily be damaged.

The

grain quality of 16mm was better. Kodak introduced with 16mm a reversal

developing process with variable second exposure. It did away with the procedure followed so

far to have negative film copied onto positive stock. As a result the costs were reduced to only

1/6 of the negative/positive process.

In later years a sound track was added on one side of the film, sacrificing one row of perforations. It was

accepted as an SMPE standard in 1932.

Split 35mm had always been popular as an alternative gauge. The American Sinemat camera/projector used it with perforations on one side in 1915.

|

Two years later the Movette camera and projector appeared for non-flammable 17,5mm stock. It had round perforations on each side.

|

In the twenties Pathé, when considering a new size of film for projectors used for shows in places in the country where no cinema was operating, also opted for 17,5mm. An optimum use of the film width was obtained by expanding the image and reducing the size of the perforations on both sides.

|

The Pathé Rural was obtainable from 1926. Pathescope, Great Britain, followed with the Pathé Rex projector only in 1932. At the same time a film library was made available with well-known films of that era. In 1932 sound film was introduced - the sound track replacing one row of perforations as in 16mm. Although 17,5mm en joyed some popularity before the war - it was used in 4823 cinema's in France - it disappeared in Great Britain in 1939. In France in the first war years as the German occupation power did not permit off-gauge films be shown for censorship reasons.

|

|

The death blow was given to this attempt when Kodak introduced 8mm film in 1932. 16 Mm was given twice the number of perforations. First one half of the film was exposed. Thereafter the reel was turned and the other half was shot. After processing the film was slit in the middle and the two 8mm halfs spliced together. In this manner as many frames were available on the 25ft small reel as on 100 ft 16mm film.

Because changing reels in the middle proved to be cumbersome a number of manufacturers introduced straight 8mm wound on 50 ft reels (Univex, Bell & Howell), or in cassettes (Agfa). Because of the lack of uniformity resulting in limited availability straight 8mm did not catch on.

In spite of its advantages nine-five lost field. Kodak had acquired a main share in Pathé in the late twenties. It had no interest in pushing that size actively. The supremacy of 8 and 16mm lasted for a considerable number of years. Yet there were attempts to introduce for the amateur economic widescreen sizes.

In fact in the first year of WW2 in the German magazine 'Film für Alle' J.Pauli of Berlin proposed using first one half of the 16mm size, turn the film around and then expose the second half. It involved holding the camera vertically and the use of a mask. The projector would need a prism to project a horizontal wide-screen image. Once one half of the film was projected it needed to be turned over in order to project the opposite half. How a film was to be edited without interfering with the opposite frames was not gone into wisely.

|

Pathé made a more serious attempt to hook on to the popularity of widescreen in the fifties by introducing a duplex and monoplex format in 1955. 9,5mm was double perforated and split in the middle to a 4 3/4mm size which was to be projected horizontally in widescreen. It was an ill-conceived idea. The public showed no interest at all. Few cameras and projectors were sold. The venture was abandoned soon and forgotten in no time. Available stock was converted to the classic 9,5mm size.

The 4 3/4 mm Lido/Orly Duplex cameras and the  Monaco Duplex projector have become rare collectors' items.

Monaco Duplex projector have become rare collectors' items.

Eight millimetre also underwent a transformation in 1965. The frame image was enlarged by 50% by using smaller vertical perforations. The so called super 8 film was supplied in 50' 8mm cassettes (having a striking resemblance to Meopta cassettes introduced years before). As from 1973 with magnetic sound stripe. Fuji attempted to introduce a far better conceived single 8 mm system but could not compete with Kodak.

|

For semi-professional use double super 8 was supplied in the manner of standard 8mm on 16mm 100 ft. reels. It gave far better results because the film passed through the precision film gate of the camera instead of that of the magazine. In addition to the larger frame size and the improved emulsion super 8 compared well with 16mm of the fifties. No wonder that 16mm was hardly used anymore by amateurs.

|

As stated before widescreen became popular in the fifties. However, it was proceeded by various attempts in the past, even in the nineteenth century as we have seen before, followed by:

All these ventures did not last for much longer than a year. In the fifties another series of attempts were made to introduce large film sizes for widescreen. To name a few:

|

|

In the seventies followed IMAX (1970), OMNIMAX (1973), Cinema 180 and others with horizontal position of frames on 65mm negative film. Special theatres were built to accomodate the projectors and ultra wide screen. Specially built projectors were needed because the film could not be pulled through anymore by claw. In the Imax system it is transported by a wave motion. Thanks to the air pressure gate precision, projection on a 180º 100 ft. width screen has become possible.

From the foregoing it is clear that standardization was dictated by the economical power of one or more manufacturers. One result was the universal acceptance and growth of the medium for amusement, information and in some cases as an art form.

For the collector hard to find off-gauge equipment/films are a true hunting-ground. In particular the sizes that were never heard of anymore. One may still profit from the relatively low prices as compared with photographica. 8, 16 and 35mm equipment/films are often offered for sale, but it becomes more difficult with 9,5, 17,5, 22, 28mm and all the other sizes mentioned.

One hundred years of cinema has yielded almost one hundred film gauges from 3mm to 75mm. The smallest of 3mm was developed in 1960 by Eric Berndt for NASA to be used in space flights. It had a centre frameline perforation. The largest was employed by Lumière in 1900 for large screen presentations at the Paris Exposition.

Most of these film sizes have been relegated to oblivion, much to the detriment of its inventors/manufacturers. Each size has its own history.

Certainly I have not mentioned all of them. Here are some more sizes:

|

For further info on the apparatus mentioned see my List and Links below. Consult also my Collecting vintage cinematographica page.

© Michael Rogge 2022

This article was published originally in Dutch in the quarterly of the Fotografica Society, Netherlands, in 1996 and updated later on.(click)

|

|

On the web since 6 December 1996. Latest update: December 2022

Return to index-page